GPS powers everything from self-driving cars and autonomous drones to robotics and mapping applications. The Global Positioning System works by receiving signals from a constellation of satellites and computing your precise position, heading, and velocity. Machines rely on this data for tasks such as navigation, localization of objects detected by sensors, and determining vehicle orientation.

To make working with GPS receivers easier, especially on Linux systems, we use gpsd — a daemon that collects GPS data and exposes it in a simple, programmatic way. In this guide, you’ll learn what gpsd is, how it works, and how to use gpsd in Python to read GPS coordinates.

Table of Contents

What is gpsd?

gpsd is a background service that communicates with GPS receivers (over serial, USB, Bluetooth, or network connections) and exposes their data through a standardized interface. It collects the incoming NMEA or binary messages, parses them, and provides clean data in JSON format through a TCP port—by default, port 2947.

The advantage is consistency. Instead of writing custom parsers for every GPS module, you can connect to gpsd and receive position, velocity, and time information in a unified structure. Multiple client applications can also access the same data simultaneously, which is useful in a robotics setup where multiple subsystems may need GPS information at once.

gpsd is your translator, turning that incomprehensible spaghetti into structured JSON or other formats your programs can actually use.

Installing and Running gpsd

Before we start with the daemon itself, we need a GPS device. This could be a USB GPS dongle, a serial GPS receiver.

Now that the gps receiver is connected to the computer, let us install gpsd:

sudo apt update

sudo apt install gpsd gpsd-clientsThe gpsd-clients package includes utilities such as cgps and gpsmon, which allow you to monitor the GPS data stream. Start the service and point it to your GPS device:

sudo systemctl enable gpsd

sudo systemctl start gpsdIf you’re unsure of the device path, check connected serial interfaces using:

dmesg | grep ttyYour receiver will likely appear as /dev/ttyACM0 or /dev/ttyUSB0. In my case, it is /dev/ttyACM0.

To verify that gpsd is working, run:

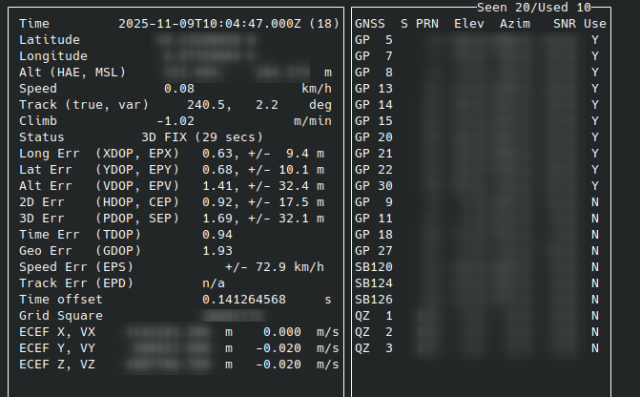

cgps -sThis opens a terminal dashboard showing live GPS information in human-readable form.

Understanding the cgps Output

When you run cgps -s, you’ll see a live dashboard with several fields updating every second. It’s a real-time snapshot of what your GPS receiver is reporting through gpsd. Not every field is equally important, but understanding the key ones will help you interpret and validate the data for self-driving or robotics applications.

Here are the most relevant parameters and what they represent.

Latitude (lat) and Longitude (lon)

These indicate your current position on Earth in decimal degrees.

Example:

lat: 37.7749 lon: -122.4194Positive latitude values are north of the equator, negative values are south. Similarly, positive longitude values are east of the Prime Meridian, and negative are west.

In most robotics and self-driving contexts, you’ll later transform these into a local Cartesian frame—like ENU (East-North-Up) or UTM (Universal Transverse Mercator)—for path planning and control.

Altitude (alt)

This shows your height above mean sea level, in meters.

Example:

alt: 18.3 m

GPS altitude is less reliable than horizontal position because of satellite geometry and signal noise. Still, it’s useful when combined with IMU or barometer data, especially if you’re building 3D maps or driving in hilly terrain.

Speed and Heading

The spd field represents ground speed, typically in meters per second (or sometimes knots, depending on your GPS unit). The track field—sometimes shown as “Course” or “Heading”—represents the direction of travel, measured in degrees clockwise from true north. (Note: Course and Heading are different terms and cannot be used interchangeably. Course is the direction of vehicle travel relative to true north whereas heading is the direction in which the vehicle is pointing. As a simple example, assume your vehicle is pointing in 10°, that means, heading is 10°. If you drive in reverse, your course will be 190°.)

Example:

Speed: 4.12 m/s

Track: 87.4°In self-driving cars, these values are critical for motion estimation. The vehicle’s control system uses them to predict short-term movement, smooth trajectories, and validate odometry data.

Time (time)

GPS timestamps are given in UTC.

Example:

time: 2025-11-04T14:22:36.000ZThis is the precise moment when the fix was computed. Accurate timing is essential for sensor synchronization—for example, aligning LiDAR, camera, and IMU data streams in ROS 2. Since GPS provides atomic-clock-level precision, it’s often used as the global time reference in distributed robotic systems.

Fix Mode (status)

The status field indicates how much information the GPS has been able to calculate:

1— No fix (position not available)2— 2D fix (latitude and longitude only)3— 3D fix (latitude, longitude, and altitude.

Status: 3D FIX (2 secs)status of 3D FIX means you have a full 3D position fix, which is what you’ll want before trusting your GPS data for navigation or sensor fusion. The time in bracket shows the time elapsed since the last update.

DOP Values (hdop, vdop, pdop)

DOP stands for Dilution of Precision, a measure of geometric accuracy. In the window, you should see different attributes with Err as suffix and different -DOP in brackets, for example, XDOP, YDOP, VDOP, HDOP etc.

Example:

vdop: 1.43

hdop: 1.31

pdop: 1.94

If you see high DOP values, the satellite geometry is unfavorable—typically when satellites are clustered in one part of the sky rather than evenly distributed.

Satellites (used, seen)

In cgps window, the box on the right usually shows both the number of satellites seen (visible to the receiver) and used (actively contributing to the current fix). A minimum of 4 satellites is required for a valid 3D fix, though more satellites generally yield better accuracy and lower noise. If the “used” count drops suddenly, it often indicates poor sky visibility or signal interference.

These are the important fields of cgps that provide relevant and useful geographoc information. When this information is required in a program, the gps module of Python allows us to parse the information and provide us the data that is required.

Parsing gpsd data using Python

In one terminal, run the following so that gpsd is able to read data from the gps receiver device.

sudo systemctl stop gpsd.socket

sudo systemctl disable gpsd.socket

sudo killall gpsd

sudo gpsd -N -D3 /dev/ttyACM0In another terminal, run the Python script with the following code:

import gps

# Connect to gpsd

session = gps.gps(mode=gps.WATCH_ENABLE | gps.WATCH_NEWSTYLE)

try:

while True:

report = session.next()

if report['class'] == 'TPV':

lat = getattr(report, 'lat', None)

lon = getattr(report, 'lon', None)

if lat is not None and lon is not None:

print(f"Latitude: {lat:.6f}, Longitude: {lon:.6f}")

except KeyError:

pass

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print("\nExiting.")

except StopIteration:

print("GPSD has terminated")Wait for a few seconds so that the gps signals are received and your program should provide an output with your current location.

Some debugging tips

- If your

cgpswindow shows N/A over all the attributes, try placing the gps receiver outside your house window. GPS signals are poorly received or not received at all if they are interfered through factors like building walls, roofs, trees etc. Make sure that the receiver gets a clear view of the sky. - Try detaching and reattaching the gps receiver to the laptop/computer. Sometimes, the interface just needs to reset.

Fun Experiments With gpsd

GPS information can be useful not only in commercial industries but also in day-to-day lives. For instance, I built a tracking device for my bike so that I know its location all the time. The idea was to build an anti-theft device. It is not a full-proof system but a small fun project with raspberry pi and gps receiver. Have a look:

Feel free to extend this project by making it more reliable, for instance, what happens if there is no GPS signal, or what if the battery for raspberry pi runs out. Try it out and share your ideas/results with me on Instagram: @machinelearningsite

Conclusion

gpsd provides a clean, reliable interface for working with GPS hardware—no manual parsing, no device-specific quirks. For engineers building self-driving cars or robotics systems, it’s an essential bridge between physical sensors and the software stack that depends on their data. By using gpsd, you gain standardized access to critical information: position, speed, heading, and precise timing.

Try out some experiments and share your journey, obstacles, results with me on Instagram @machinelearningsite or just ping me if you want to have a chat ;).